(Compiled by John’s eldest daughter, M)

It was a strange thing to find a dozen or so postcards from Asimov in a small, understated box on Dad’s desk. I hadn’t known about this correspondence; you’d think Dad would have mentioned it to us at some point, given his devotion to the man! Good heavens, letters from Isaac Asimov himself?

(Of the three of us, my brother R had apparently known about “a few letters,” but not their extent nor tone. And we all knew Dad had received permission to photocopy Asimov books for his private collection, but none of us knew that permission had come from Asimov directly.)

“Correspondence” is perhaps being generous. Given the frequency of Asimov’s responses (and the nature of the exceptions), the good doctor was prolific at responding to fan mail, just as with everything else. This kind of earnest fan engagement is rare from authors, and it’s amazing to me that Asimov made the time for it given how busy he must have been.

We have all of Asimov’s responses, but almost none of Dad’s original letters. Surprising and disappointing. He made carbons of letters to friends and family, perhaps numbering in the hundreds, and for whatever reason he chose to transcribe only Asimov’s responses — not his original letters — into his journal. We will post more material if we discover it, but given how tightly Dad was managing his massive journal, I doubt there are any “free range” copies.

Excerpts from Dad’s journal are included. Do keep in mind he was 13 when this all started.

Enjoy.

The Pre-Journal Asimov Correspondence

[Dad wrote this as a prologue to his journal when he retyped it in August 1976, at the age of 16.—Ed.]

On December 20, 1973, I became an Isaac Asimov fanatic. I have been one ever since.

Oh, to be sure, Dr. Asimov had been my favorite writer for some time before, but on the twentieth of December, A.D. 1973, for the first time, I took steps to correspond with him. That was when I crossed the line from fan to fanatic.

As I remember, my mother was the first one to suggest how to get Dr. Asimov’s address (no one thought, at the time, of the obvious method of looking in a New York phone book). She said I ought to write to one of his publishers and ask them, so I pulled down from my shelf a book printed by Doubleday and Company, Inc., and looked for the address. Unfortunately, it simply said, “Garden City, New York.” I wrote the letter on the date mentioned above and went down to the post office to find the ZIP code for Garden City. Strange to say, I couldn’t find it, so I sent my letter minus ZIP code.

Eventually, it worked its way through the echelons of Doubleday to the desk of Lawrence P. Ashmead, who was (and is) Dr. Asimov’s number one editor. His secretary (I presume) wrote me the following reply, the first answer I have in my Asimov correspondence.

![Doubleday, a communications corporation. Mr. John Jenkins, [redacted], Salt Lake City, Utah 84108. Dear Mr. Jenkins: Thank you for your letter of 20 December. Unfortunately, we cannot give out the addresses or telephone numbers of our authors. If you would like to write to Dr. Asimov, however, you can send your letter to him in care of Doubleday, and we will see to it that it is forwarded. Sincerely, Cathleen Jordan, for Lawrence P Ashmead.](https://blog.asimovreviews.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1974-01-03-Letter-from-Doubleday.jpg)

The letter included Doubleday’s address (277 Park Avenue, New York City, 10017), so almost at once, I wrote to Dr. Asimov, asking a lot of awfully personal questions.

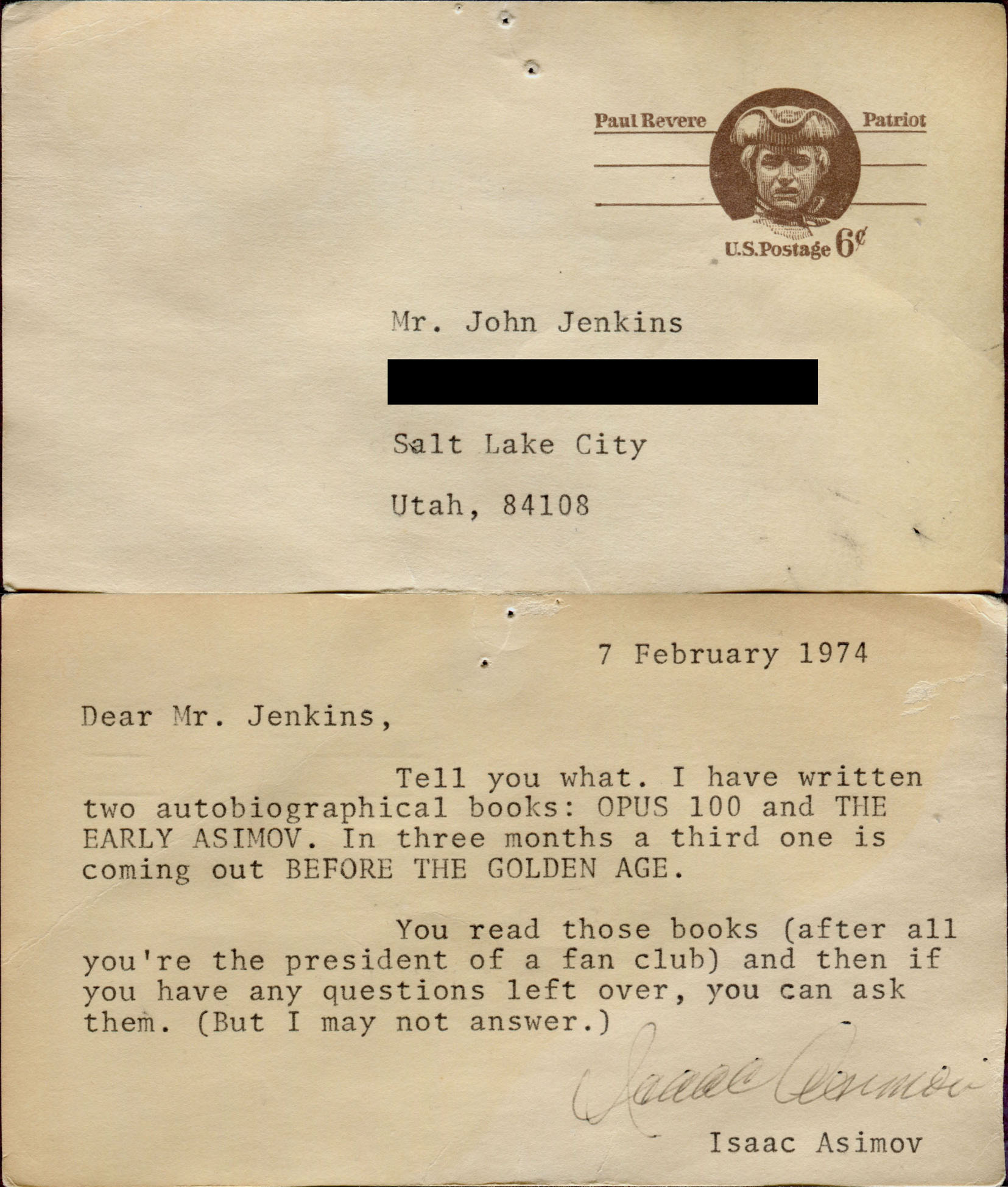

Doubleday, I have learned, forwards all fan mail to Dr. Asimov at the end of the month. Although my first letter was written in January, Dr. Asimov’s reply (which delighted me no end) wasn’t written until February. It is as follows:

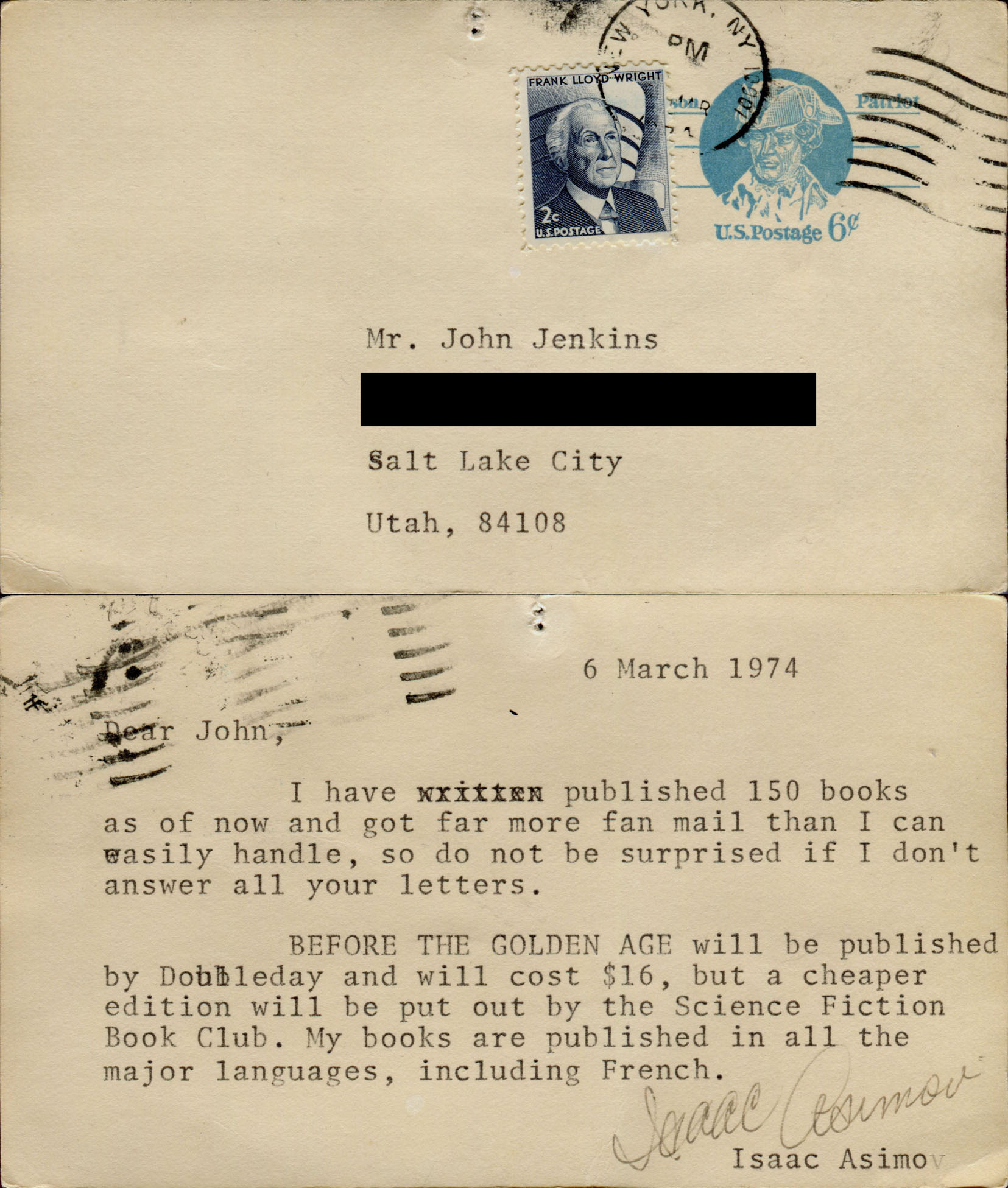

That post card, it seems, is pretty much his standard reply to all first-time correspondents. Although it is awfully impersonal, it didn’t discourage me–at once, I rushed to the library to find Opus 100 and The Early Asimov (I now have copies of both, and my second letter went out to Dr. Asimov. (I’m sorry that I can’t reprint the letters, but I’m afraid the thought of making carbon copies just didn’t occur to me at the time.) Dr. Asimov’s reply was:

It seems that in my second letter I asked: 1) how many books he had published, 2) publication information about Before the Golden Age, and 3) if his books were published in French (which I was studying at the time).

Halfway through March, it became impossible for me to wait any longer, and I wrote a third letter. In it, I said one thing of importance: “Dr. Asimov, I’d like to write a biography of you. Don’t answer if it’s all right,” or something to that effect. He didn’t answer, and “The Great Asimov!” sprang into being. [This is an ambitious biography Dad wrote when he was about 15. It’s 220 pages typewritten, double spaced, and yes, we have all of it.—Ed.]

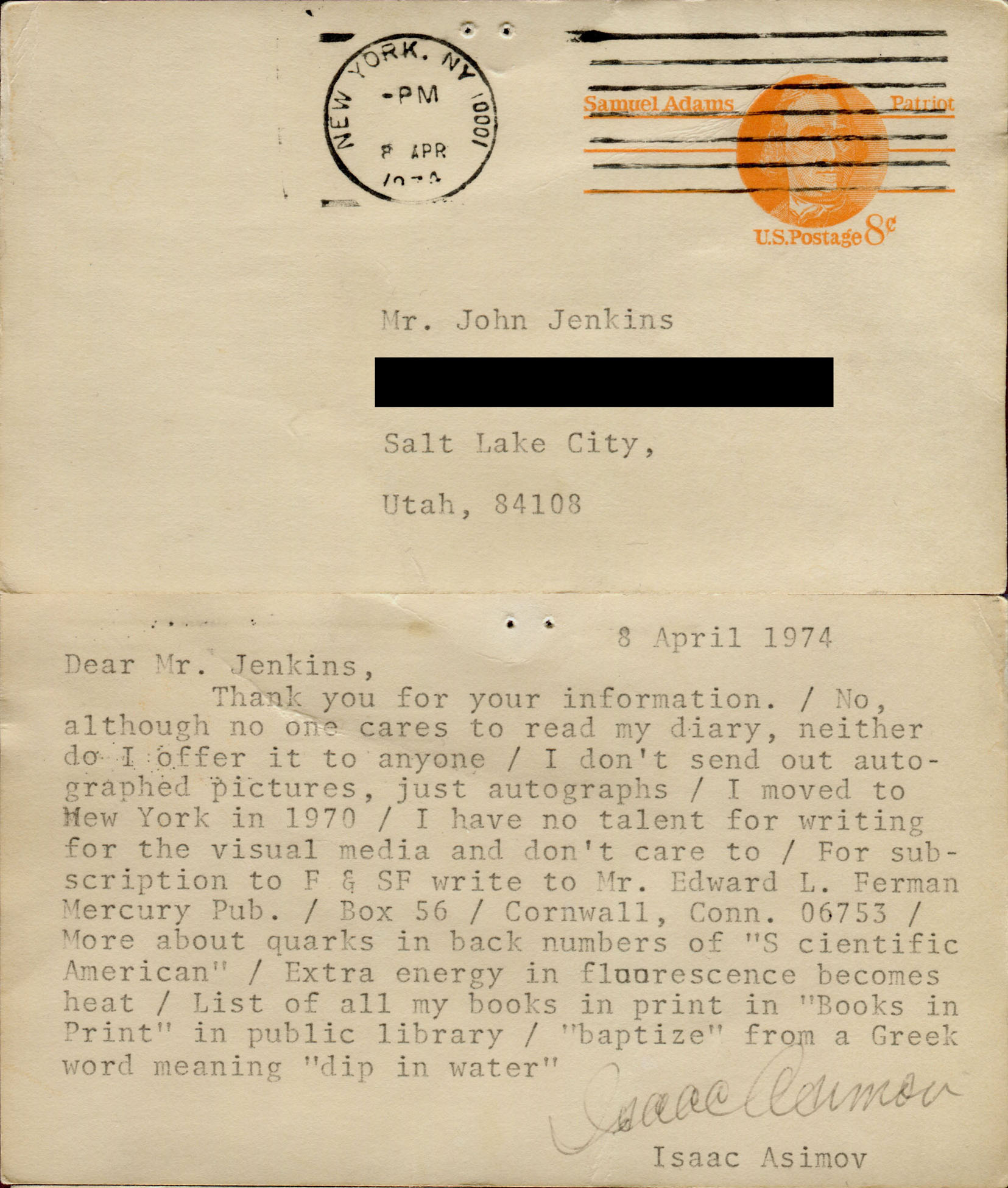

In my fourth letter, I gave him certain information about the larval stages in insects (he made a blunder in Twentieth Century Discovery) plus a lot of other things, so I got the following reply:

(As to why, in the second letter, he called me “John,” but in the third reverted to Mr. Jenkins: In the second, I asked him to call me “John.” since I didn’t deserve the respect of “Mr. Jenkins.” I assumed that he would remember, and he didn’t so I am occasionally called “John,” occasionally “Mr. Jenkins” and occasionally nothing, but more about that later, perhaps.)

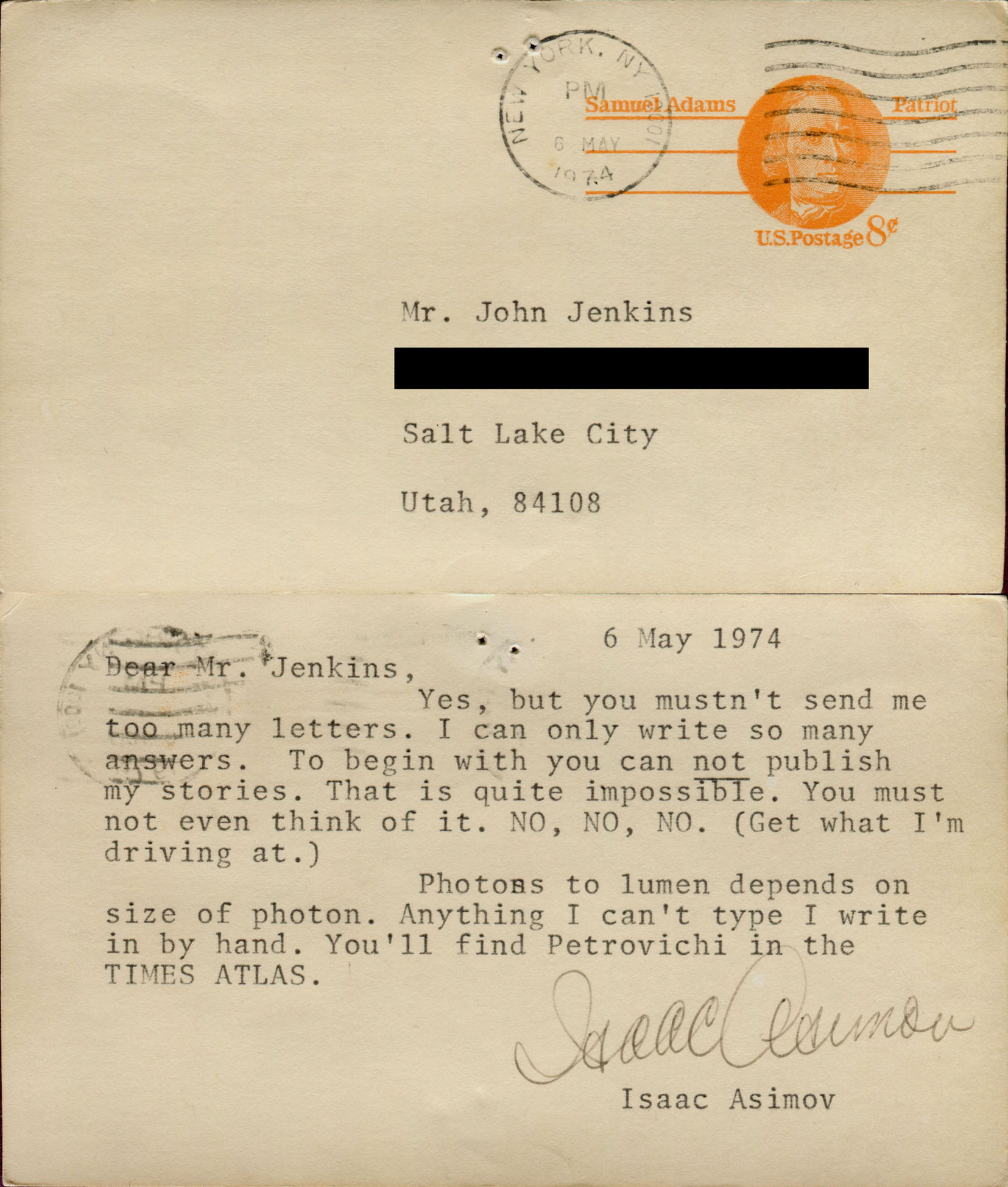

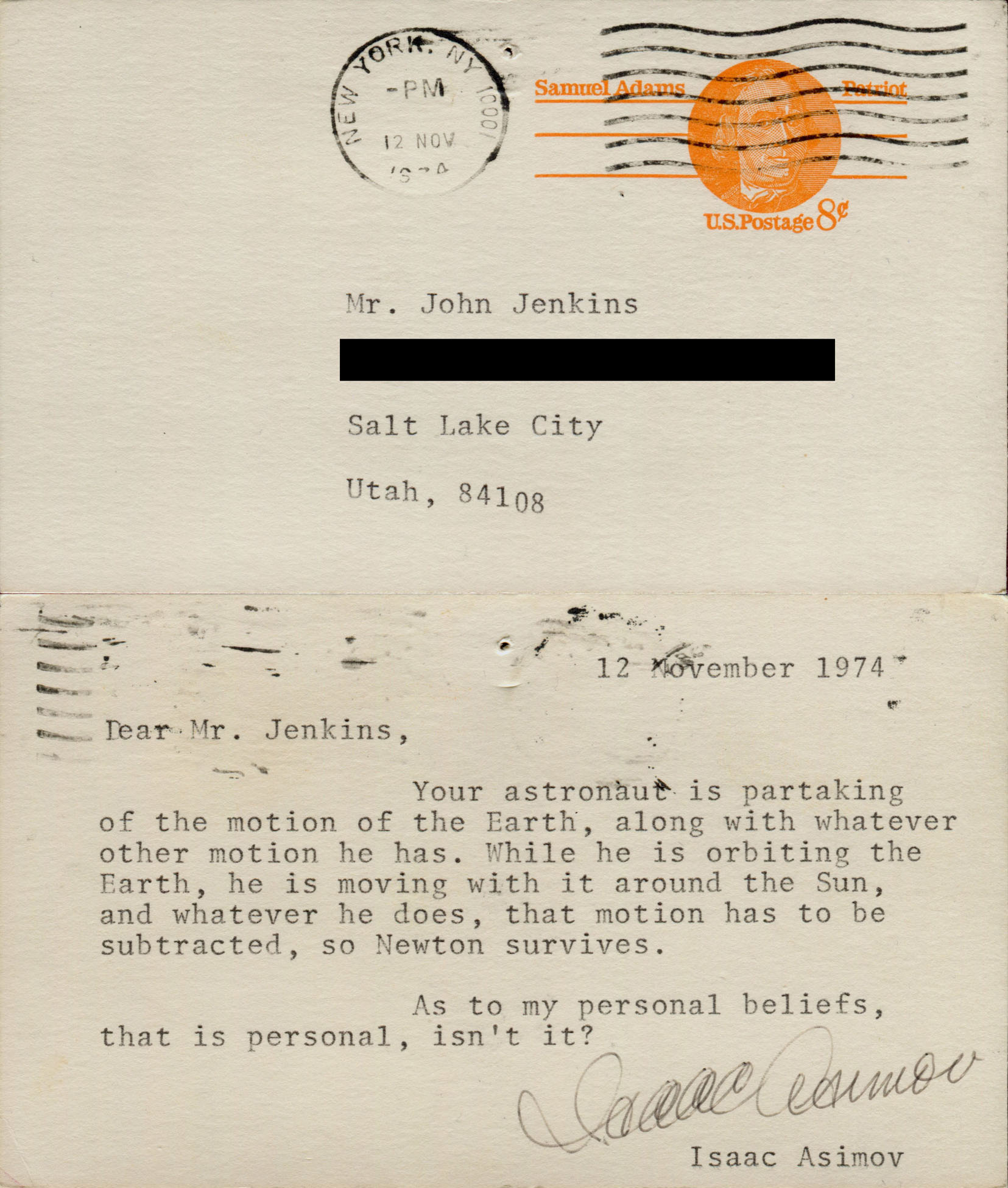

The last post card I received before starting the Journal had the profoundest effect. Because of it, it was until August and September (I think) before I wrote again, and both times the letters were religion oriented and not answered (thus are the three letters he never answered, numbers three, six and seven). His fourth post card reads as follows:

The first question he answered was concerning my request to reprint his stories in a fanzine I was considering, devoted only to him. The others are self-explanitory [sic].

16 November 1974

Today, I received a post card from the illustrious doctor. The post card was written on the twelfth, my un-birthday, and reads as follows:

I’ve received four other post cards from Dr. Asimov, one in February, March, April and May. I’ve not written him much in the last six months, but I have been serious when I have. I might quote the other letters at a later date.

But I don’t know whether or not he’s an athiest [sic]. Oh, well.

31 January 1975

Today, I again undertook to write Dr. Asimov:

Dear Dr. Asimov,

I am sure that you remember the experiment conducted in 1953 by Stanley Lloyd Miller, wherein he showed that amino acids could be produced in conditions on Earth about four billion years ago.

For a science fair project, myself and others have undertaken to repeat this experiment. We are using your book, Photosynthesis, as our guide to setting up the apparatis [sic], but there is one thing which is bothering us.

According to you, Miller produced hydrogen cyanide. This is a drawback. We would like to go through with the experiment, but we are terribly afraid that we might spring a leak despite elaborate precautions, or that the entire thing might blow up, filling the immediate area with hydrogen cyanide, a thought that we find somewhat disquieting.

So, we need to know exactly how to neutralize (you know what I mean) hydrogen cyanide, just in case it may leak into the atmosphere. Seeing as you are a biochemist, we felt that we could ask you. So, how does one neutralize hydrogen cyanide?

Second, could you recommend a book that would tell which solvents to use, how long to use them, and which stains or chemicals to use to detect the various compounds produced (especially the amino acids)?

I read your recent article in SEVENTEEN magazine, and it delighted my English teacher no end, because all along, I have been saying that Edgar Rice Burroughs was a rotten science fiction writer, yet you praise him nonetheless.

(I also read your story in the February BOYS' LIFE, and I thought it was up to your usual level of excellence; but the paragraph on you in the same issue was terrible. I'm going to complain to them about it.)

Sincerely,

John H. Jenkins

1 February 1975

I shall send the letter off today.

In the same issue of BOYS LIFE, as I mentioned in the letter, is a paragraph on the Good Doctor. It was terrible. It claimed that he had only one hundred forty books published, that he was a professor of biology, and that the movie Fantastic Voyage was made from his book. I am therefore writing to the “Dear Abby” of the Boy Scouts, Pedro, to complain.

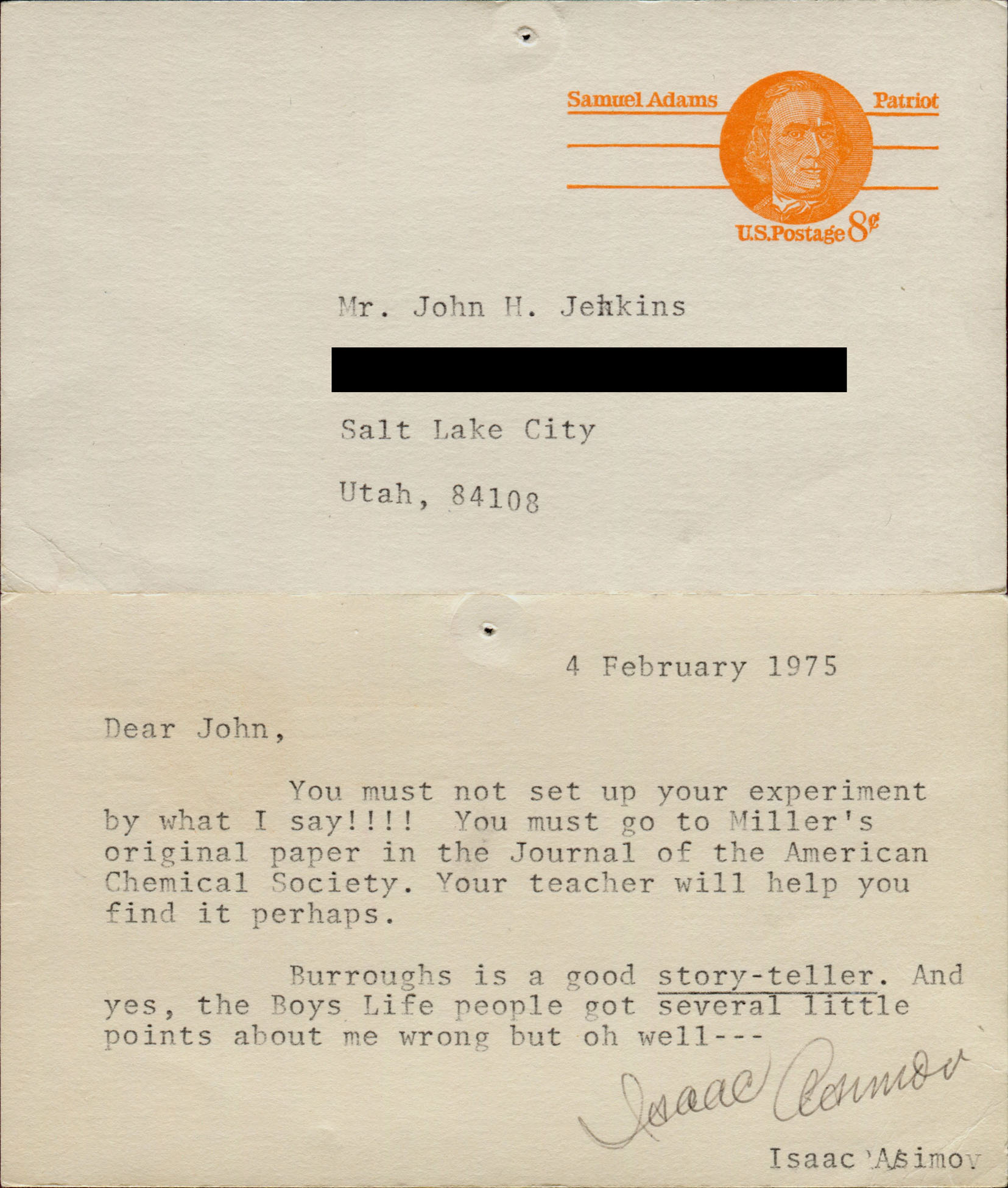

5 February 1975

Today, I received in the mail an answer to my last letter to the Good Doctor:

[…] As I finished writing the previous part of today’s entry, I looked up to my bulliten [sic] board and took at [sic] all of my other letters from Isaac Asimov, and I found, to my surprise, that the first letter by him to me is dated 7 February 1974.

It has been exactly one year since Dr. Asimov has first found out about me–a whole year.

I can’t describe the feeling that I have now that I realize that, he off in New York, and I in Salt Lake, we have both lived for one year since he first received a letter from the crazy kid John Jenkins. In that time, in that one year, I have written him eight times, and I have received six replies. Seven of the times I wrote to him, I wrote in care of Doubleday & Co., Inc., but on the eighth, I wrote to him for the first time at his home address.

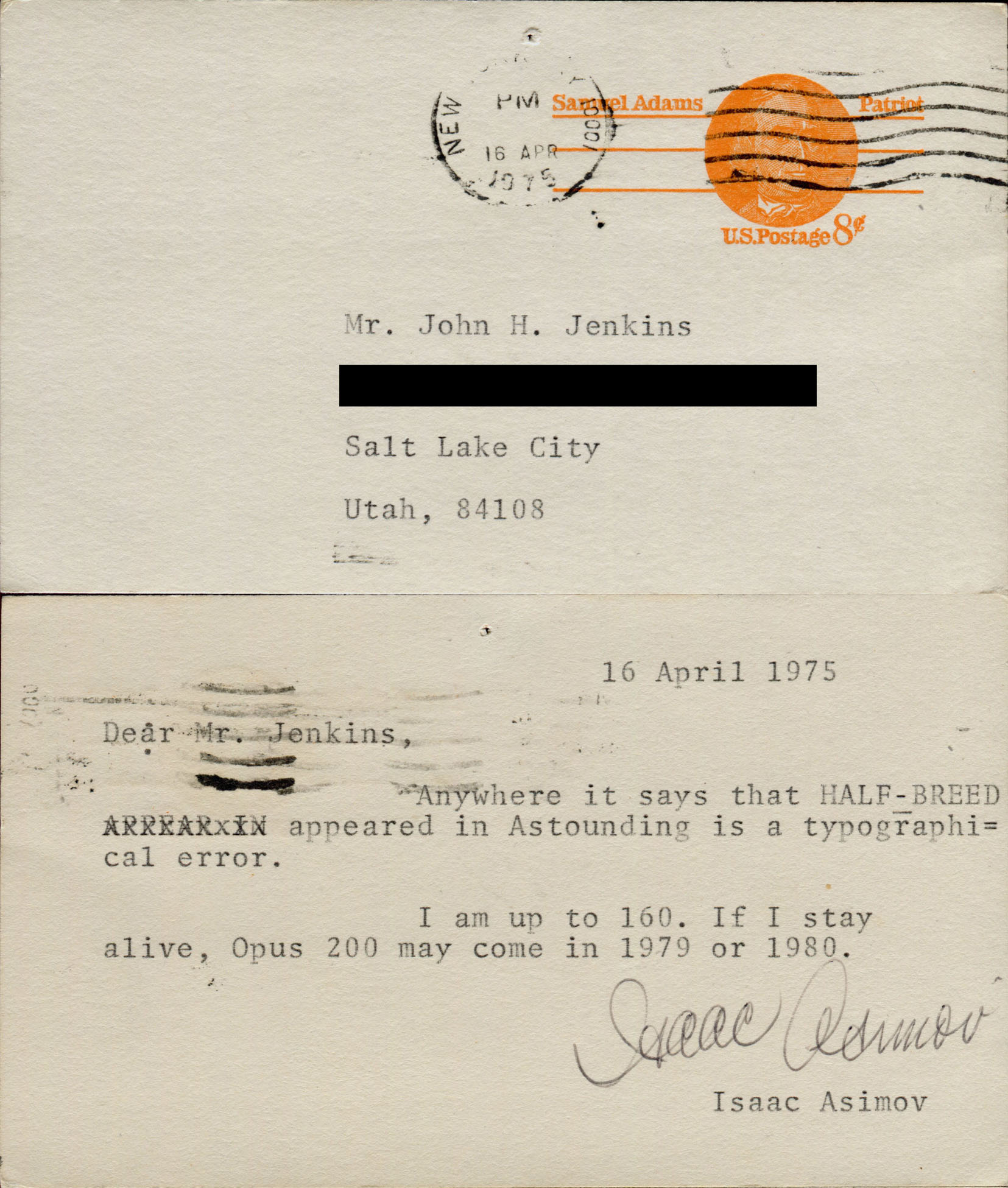

19 April 1975

Today, I received a reply from Dr. Asimov to my most recent letter:

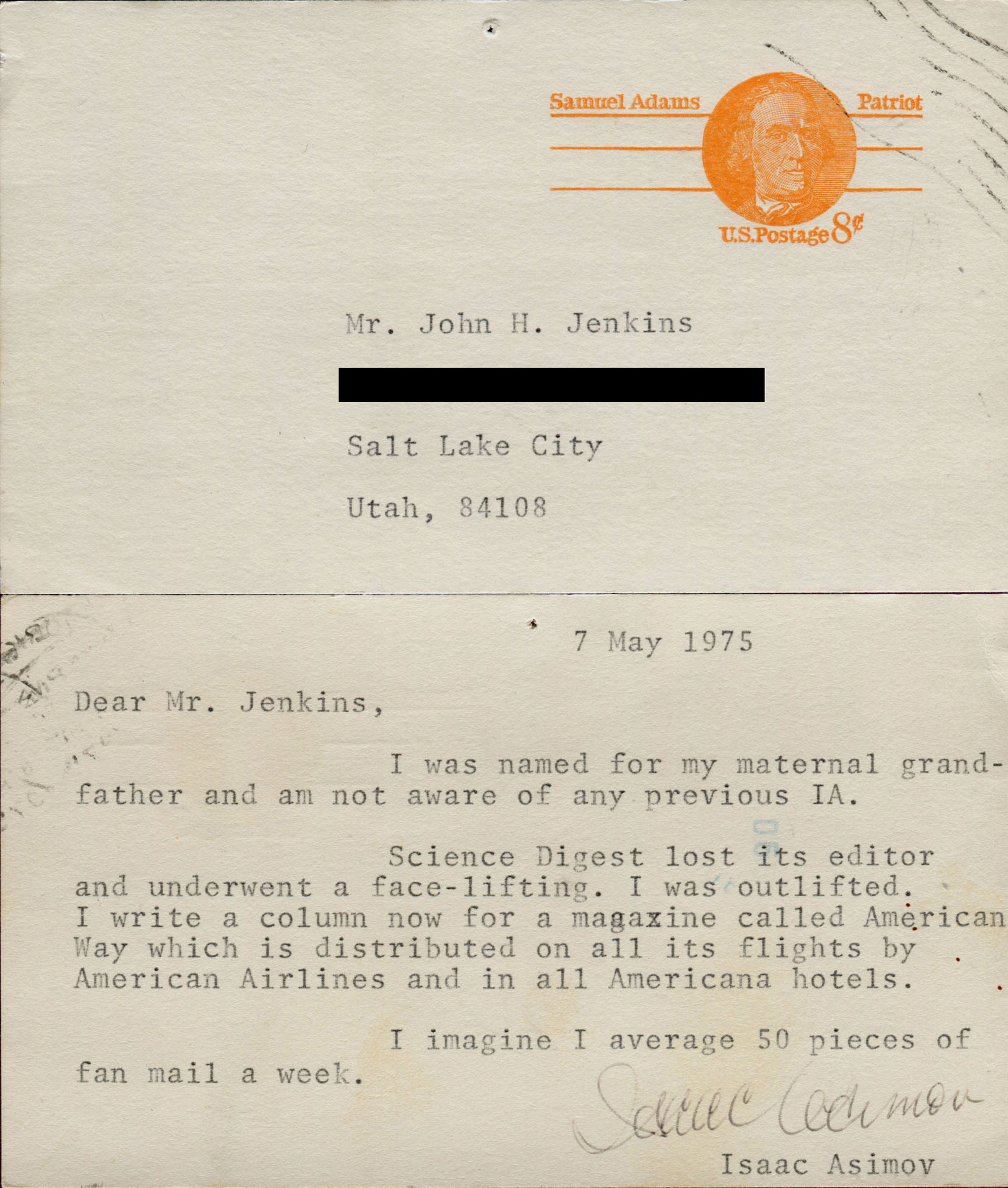

13 May 1975

Well, as you undoubtedly know, yesterday was my birthday, the one upon which I turned fifteen.

[…] I got only a few things: one thousand (!) sheets of typing paper, a record, a cake, and a stereo on which to play the record.

Today, in fact, I was much happier to see something else that I got:

This is the eighth post card I’ve received from Dr. Asimov for the eleven times I’ve written him. I don’t plan to write him again for a while.

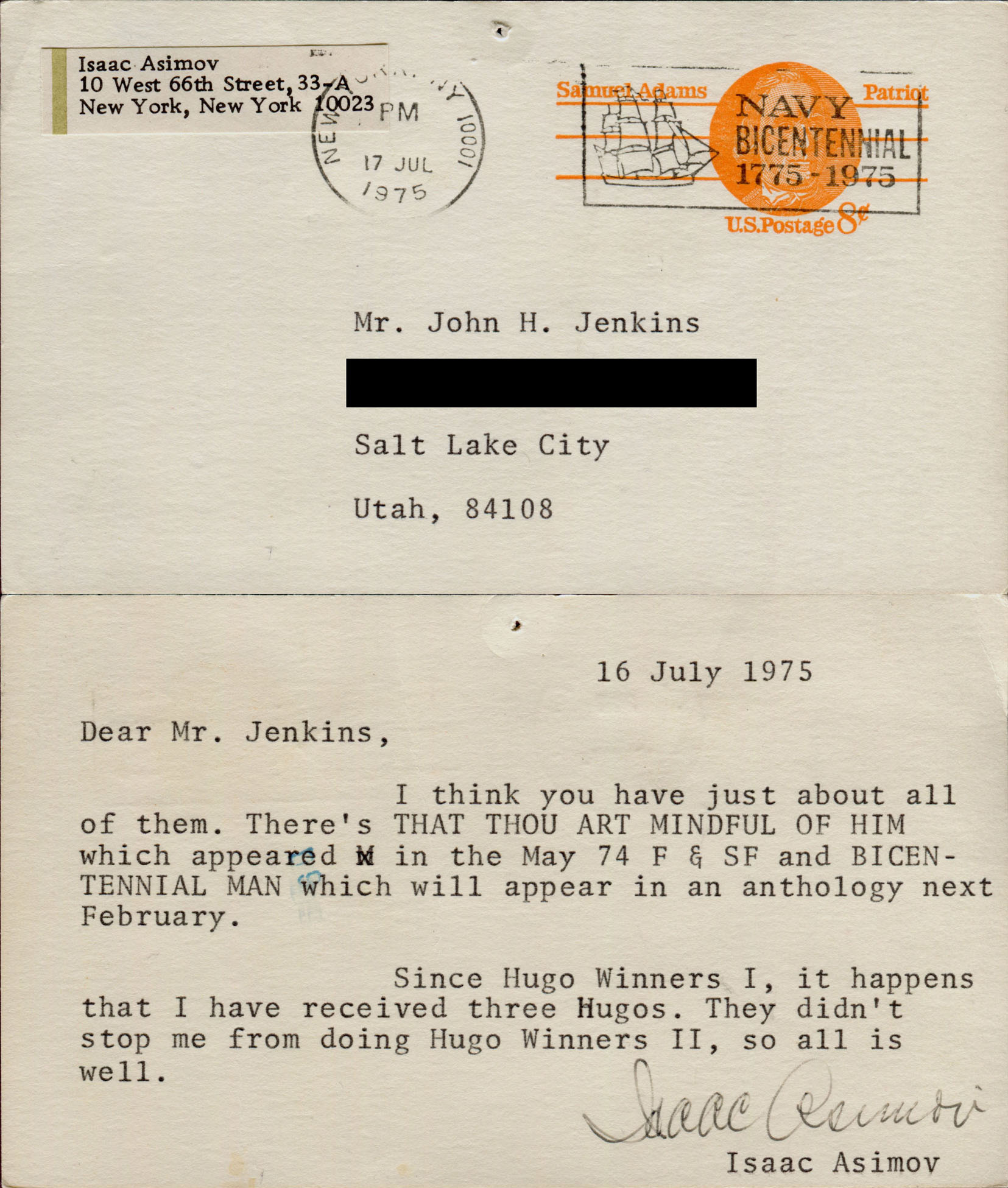

21 July 1975

First of all, I’ve received an answer to my most recent letter to Dr. Asimov (on this one, he gives his return address, which shows that he’s moved: 10 West 66th Street, 33-A/New York NY 10023):

(By an interesting coincidence, “That Thou Art Mindful of Him” is his novelette which has been nominated for a Hugo award this year. In my letter, I expressed a fear that if he wins, he may be disqualified from doing The Hugo Winners, volume III, but it doesn’t seem to bother him any.) [He since has. John–11/29/78]

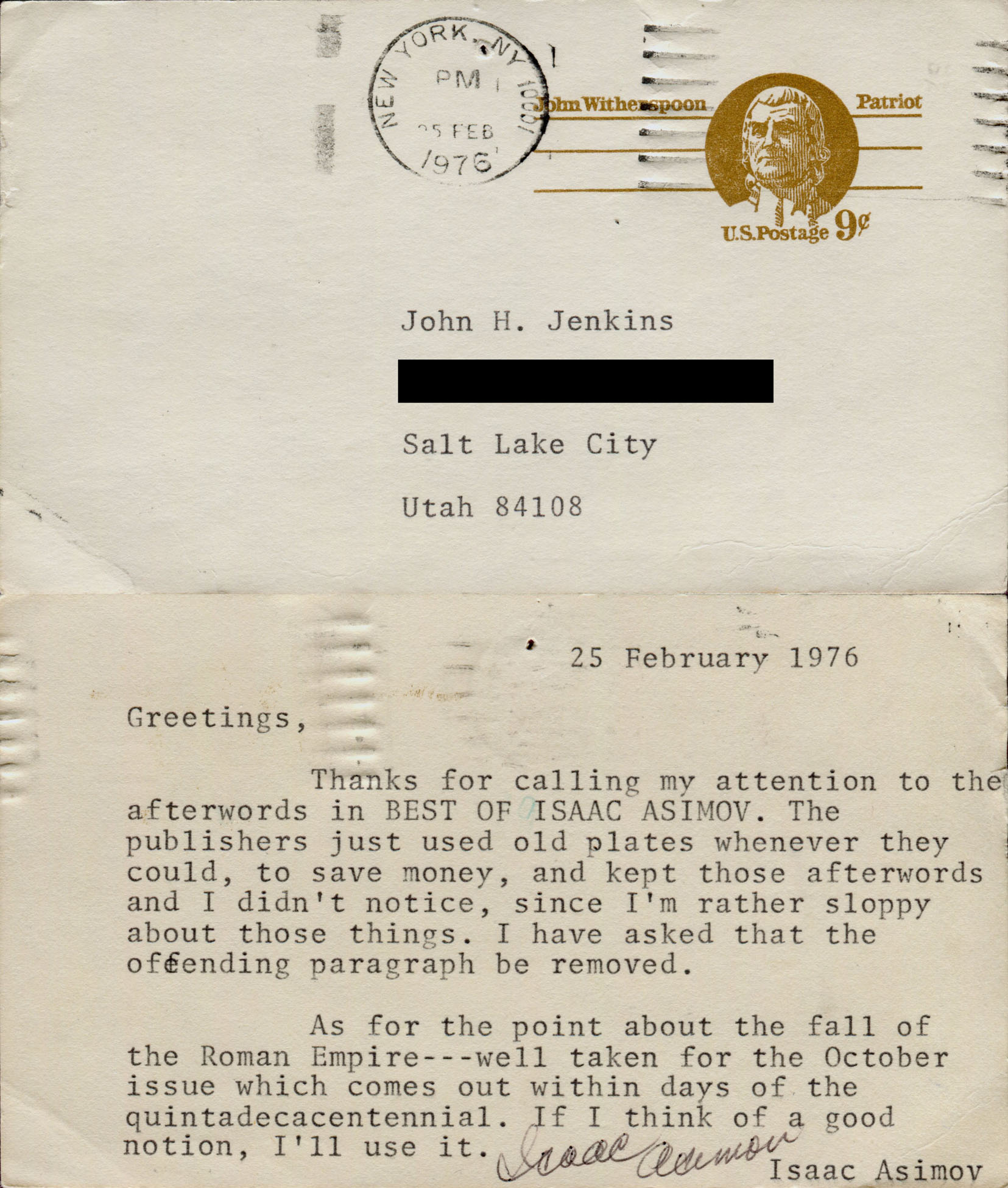

29 February 1976

Last Sunday, I wrote a letter to Dr. Asimov, as I have done several times in the past (twelve, to be precise[…]). And, yesterday, I received my traditional post card answer (the tenth) […].

“The October issue” refers to the October F&SF, in which Dr. Asimov has a monthly column. I had suggested to him that perhaps he could write an essay on Rome for the quintadecacentennail [sic].

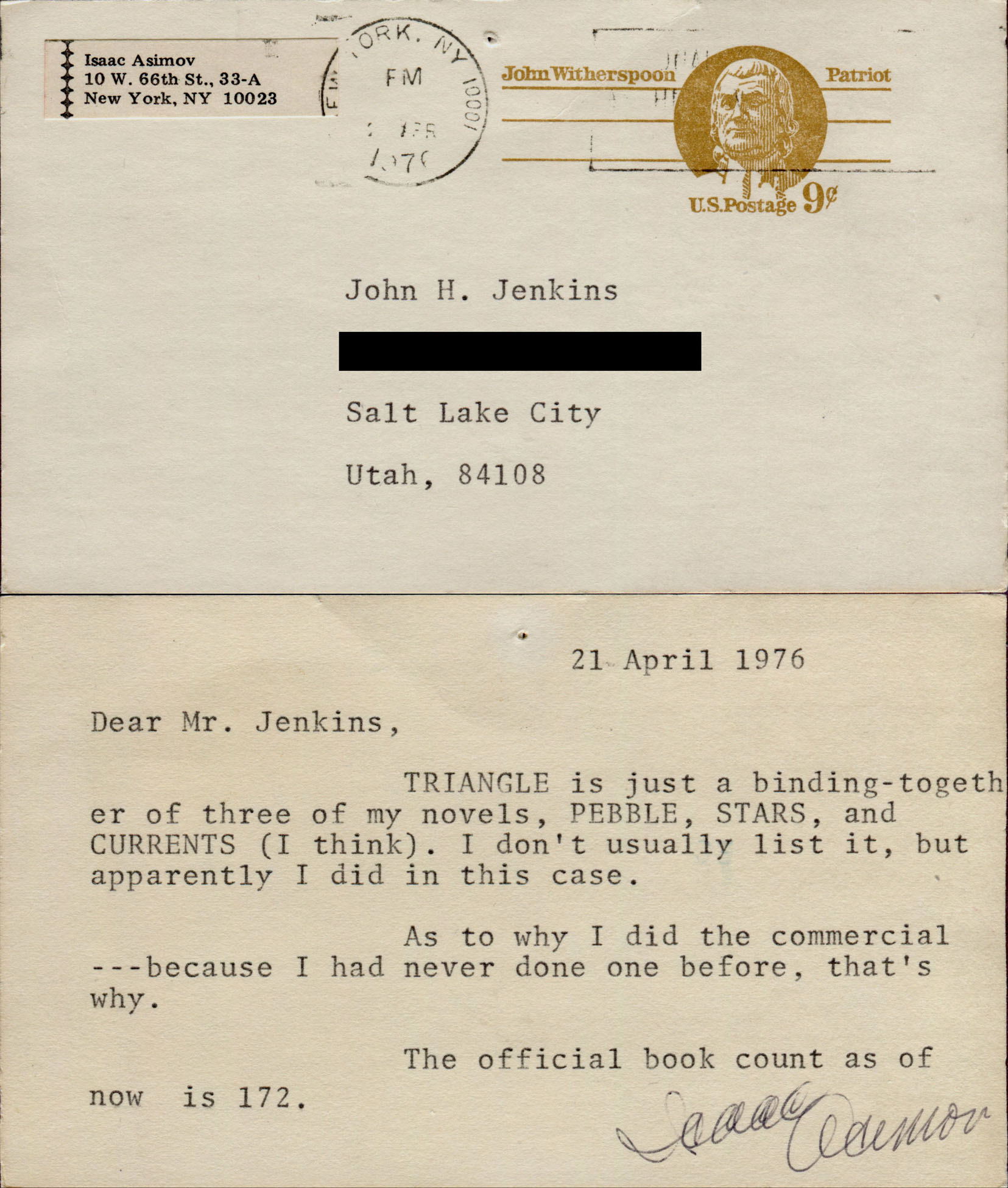

25 April 1976

Yesterday, I received an answer from Dr. Asimov to my fourteenth letter I have written to him over the two years and whatever since February of 1974. It reads as follows:

I rather think that he’s angry with me, because in his last post card, he started out with “Greetings,” but here he is back to the stilted “Dear Mr. Jenkins.” Indeed, in the last post card I got the distinct impression that he likes me (which is improbable), but here, I don’t. But, then, perhaps I was overly rude in complaining about the commercial.

[From Dad’s journal on 21 March 1976: “Would you believe that Isaac Asimov has bent so low as to appear on a television commercial? It’s almost enough to make one turn in one’s Isaac Asimov post cards in disgust.” I know Asimov had been in some magazine ads, including some for the TRS-80 (which in retrospect might explain why we owned one), but I can’t find the TV commercial Dad is talking about. Insights are welcome.—Ed.]

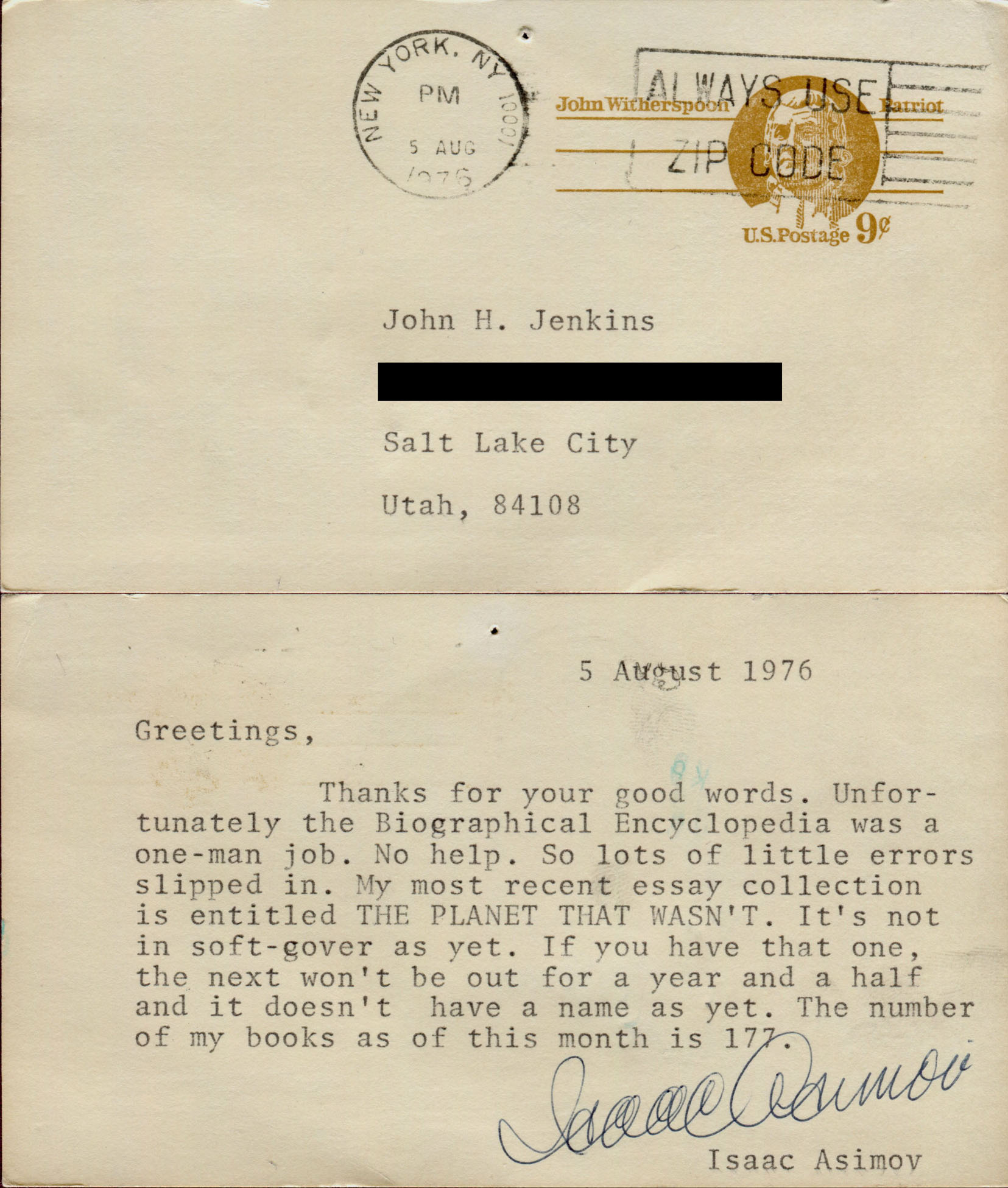

13 August 1976

So he’s back to “greetings” […]. I wonder why.

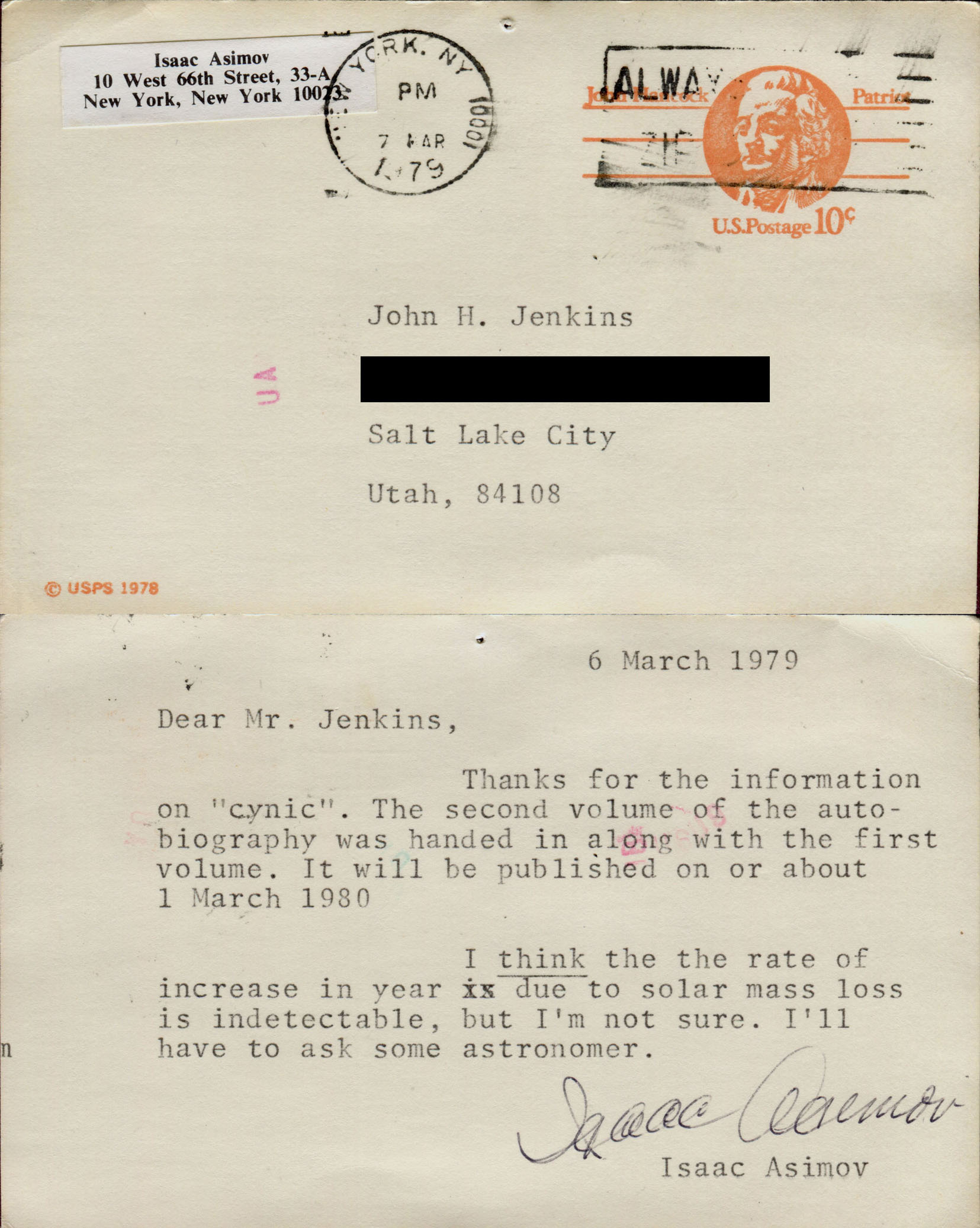

4 March 1979

I’ve written to Dr. Asimov again. That’s something I haven’t done for two-and-a-half years […]. This time, however, I kept a carbon of my letter, and I’ll give it to you [the journal reader] when I get his reply. Odd, odd indeed. [The carbon is nowhere to be found 🙁 —Ed.]

11 March 1979

So much for reading the end of his autobiography before August of 1981.

[…] I may just write Dr. Asimov again before too long. You see, when down at the Library yesterday, I decided that the time had come for me to check out any books of his I haven’t read yet (I decided that because it seemed logical they might have bought some new ones in the three or four years since my collection passed theirs in size and I finished reading theirs, anyway), and I dug up three: The Golden Door, Mars, and Quasar Quasar Burning Bright. The Golden Door has occasion to mention the Manifesto forbidding polygamy (now part of the DEC, as you well know)–and in his time-line at the end of the book, Dr. Asimov says that the Mormon Church gave up polygamy on 6 November 1890. Something big like that would never be done on 6 November, but on 6 October or 6 April, at [the LDS general] conference. I looked in the D&C [Doctrine and Covenants], and I was right. It was 6 October 1890 that the Church voted the Manifesto as binding. I don’t know how much Dr. Asimov would like my sending him an erratum sheet, but, well, we’ll see.

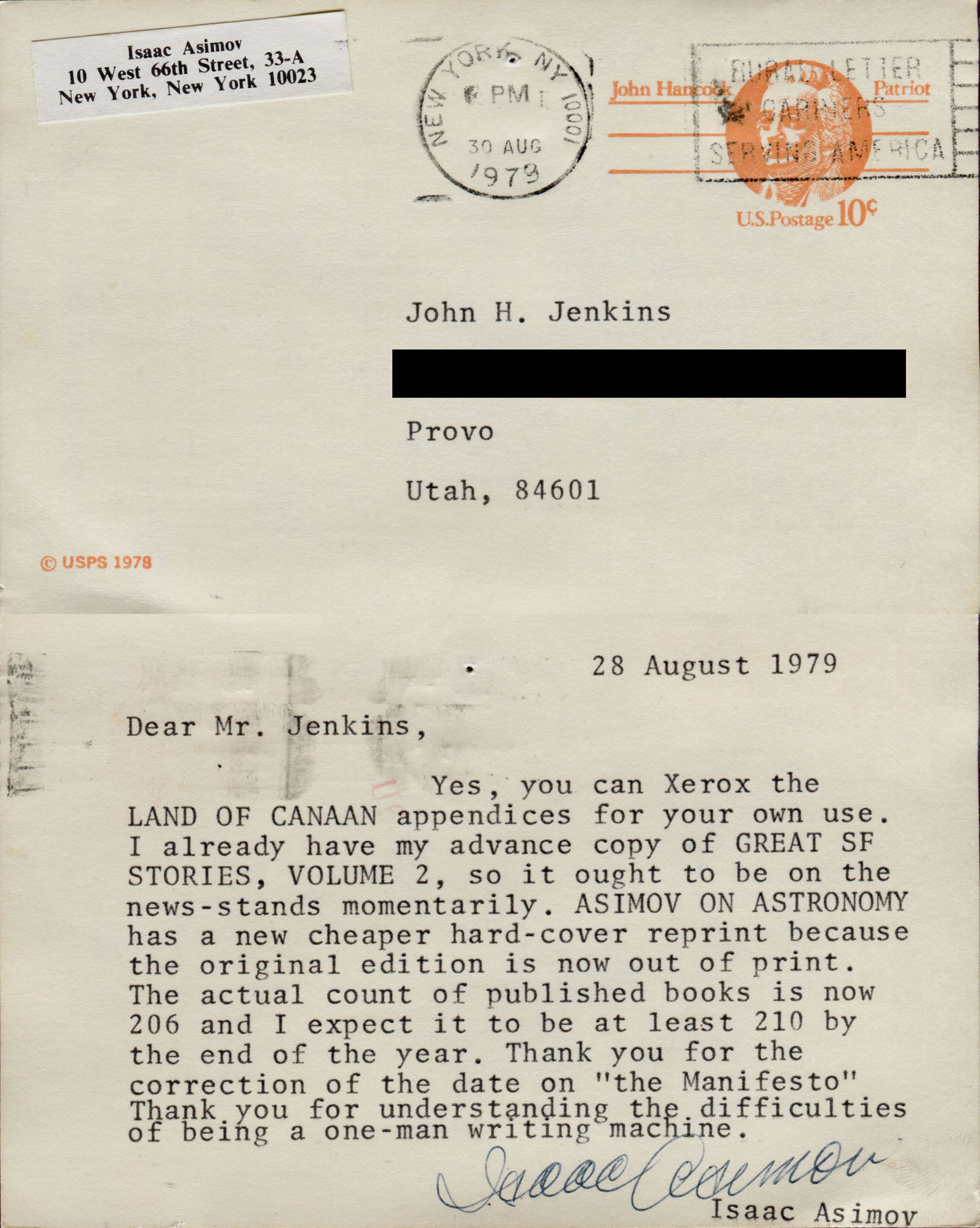

2 September 1979

I wrote Asimov on the twenty-first of last month, and, as of yesterday, I got no answer back. This means that, either he has moved since my last letter (which I doubt) or he simply didn’t answer, and I rather think that’s the case. This is the first time he hasn’t answered me for five years, certainly the first since I started the Journal, and is therefore depressing. I wonder why, though. I can guess with the other three times […]. I am very much bothered, and, since I need an answer to one of my questions, I’m just going to have to write him again, perhaps this next Tuesday but probably not since I already have just piles and piles of letters to write.

4 September 1979

So he did answer, after all. Hm. The mail was just slower than I’d expected, slower than it’s ever been before. Oh, well.

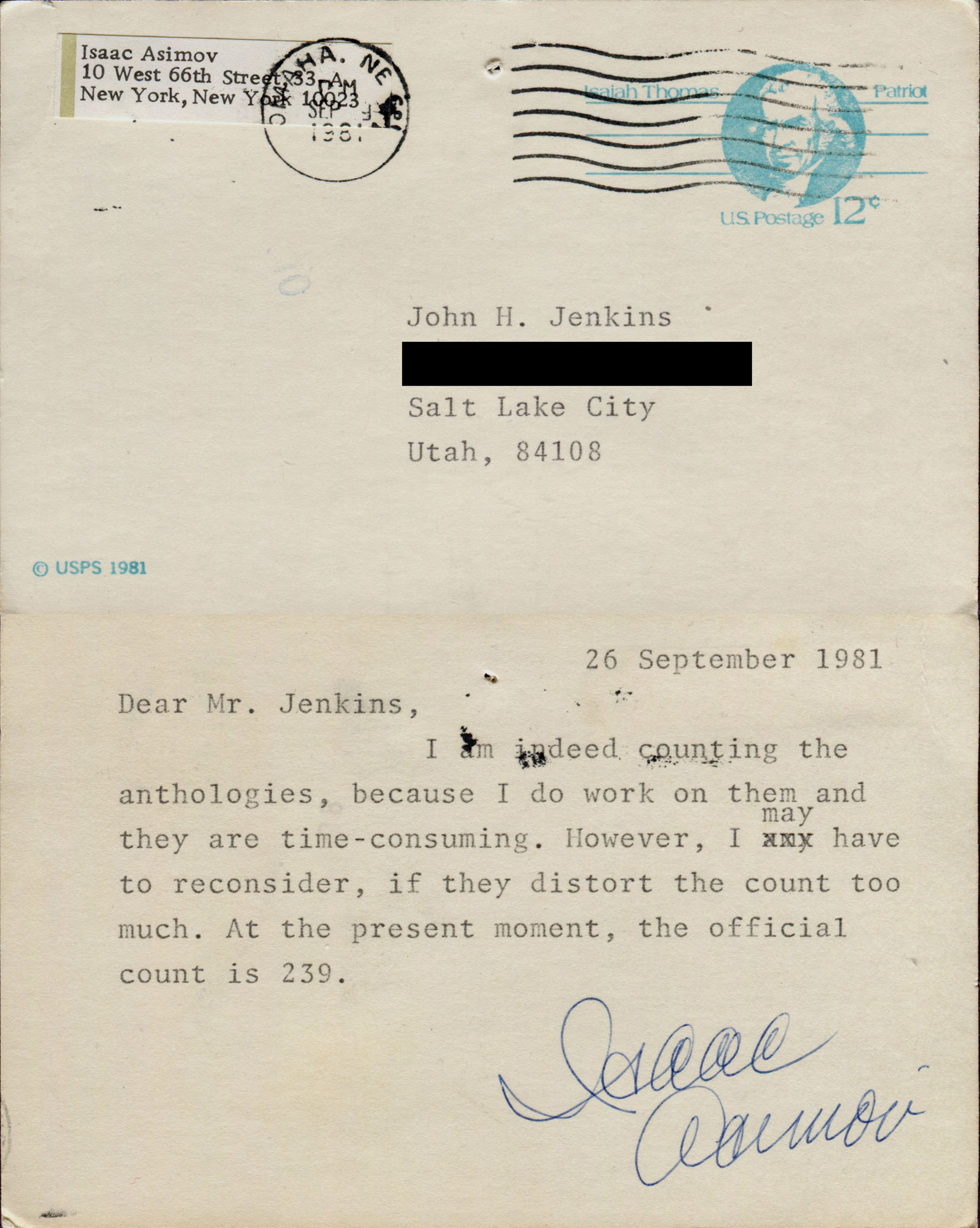

4 October 1981

This is the fifteenth post card I’ve received from Dr. Asimov, for a total of nineteen letters written to him in the last seven-and-a-half years. […] That means that, on the average, he’s written me once every six months for what is now almost an eighth of his life. He’s very good to his fans, really.

[For this one, we do have the carbon copy of what Dad sent.—Ed.]

![22 September 1981. Dear Dr. Asimov, I hate to intereppt your busy schedule, Dr. Asimov, but I have an urgent question I need your help on. I have been, for quite some time an ardent collection if vour books and I like to flatter myself that I've got the largest collection of Asimovia in the intermountain West--certainly the aargest in the state of Utah. Unfortunately, however, the money I have to buy your books is rather limited and so I can't afford to go around buying books that have your name on them if they aren't really your books. I've run into a few, then, that I'm not certain whether included [unclear] by you on your official list of Books-that-Isaac-Asimov-Has-Written. The Books in question are: *Isaac Asimov's Book of Facts*, ahd those collections of science fiction stories that you've been editing with Martin Greenberg, or Martin Greenberg and Joseph Olander such as *The Great Science Fiction Stories One* through however many there are at the moment, *The Future in Question*, and so on. If, then, you could kindly tell me whether or not you intend to count these and similar books in your official reckoning of your books, I would be very grateful. (By the way, just what is your official count of books published at the moment, anyway?) Sincerely, John H. Jenkins](https://blog.asimovreviews.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1981-09-22-Letter-to-Asimov.jpg)

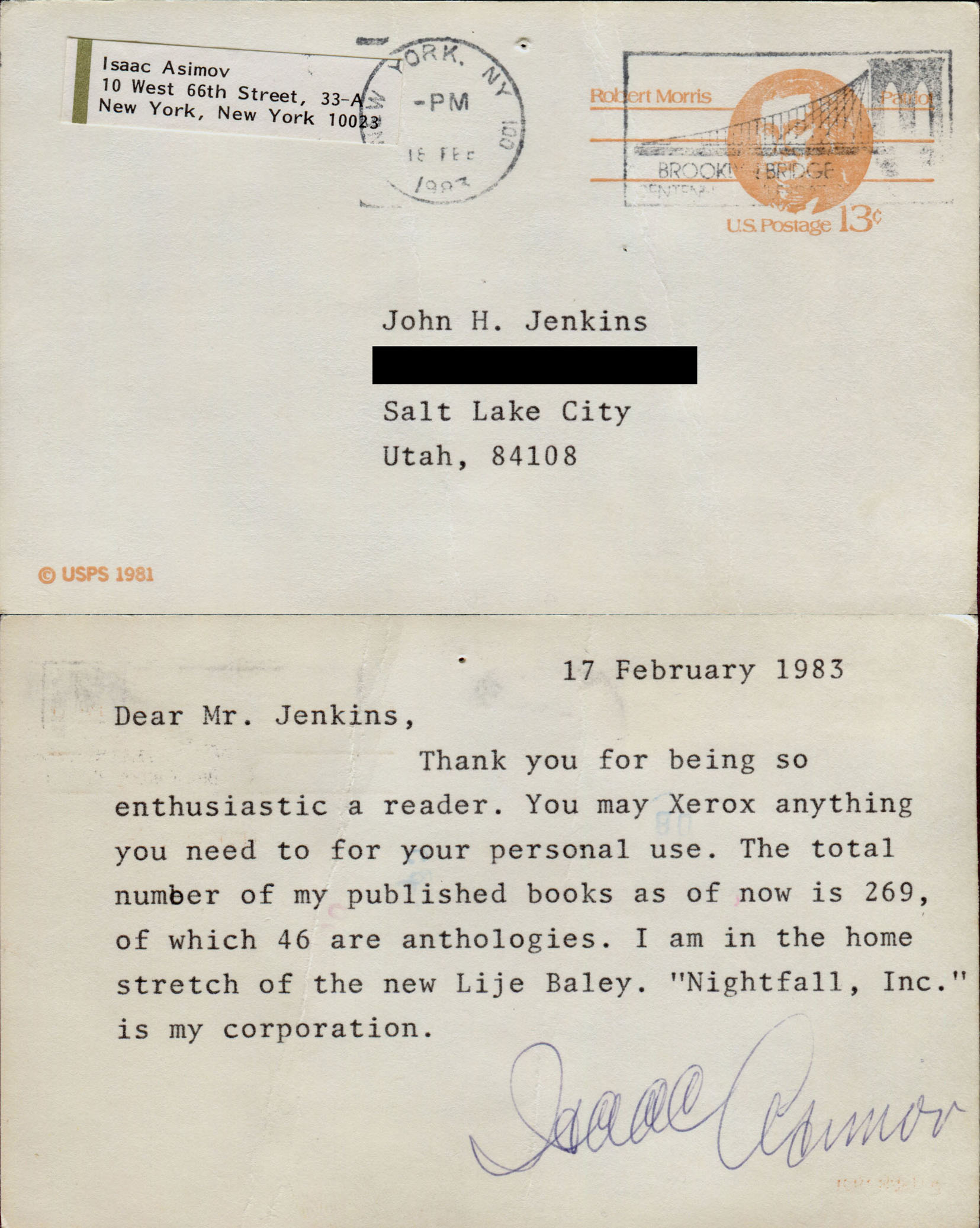

23 February 1983

[…] I received today:

3 March 1983

I Xeroxed four books by Asimov yesterday, and bought a fifth on Tuesday: Inside the Atom (1st ed.), The Kingdom of the Sun, The World of Nitrogen and The Best New Thing, and Worlds Within Worlds, respectively. That gives me 192½ out of about 270–I am within eighty, for the first time ever that I can remember. I may soon pass two hundred. In any event, I am unhappy to discover that the two Libraries in Salt Lake have so few books by Asimov which meet my three criteria for Xeroxing: 1) they must be out of print (else I could buy them); 2) I must not own them (else why spend more money on them?); and 3) Asimov must own the copyright (else I have no legal permission to Xerox the whole book). This third may change by the end of the current session of the Supreme Court, depending on their decision in the Betamax case. We’ll see.

[This journal excerpt isn’t related to Dad’s correspondence to Asimov as such, except that contains Dad’s criteria for choosing what to Xerox “for [his] personal use.” Dad photocopied quite a lot of Asimov’s books, and such copies acted as “stand ins” in his near-comprehensive collection. As time went on, and increasingly empowered by the internet, he acquired real copies of rarer and rarer material, after which time the Xeroxed copies were discarded. Discarded, of course, meant they were designated as “scratch paper” for the children to doodle upon, or to use to print unimportant documents with the family’s LaserWriter. It was a very normal thing for us to have random pages of random books on the reverse of all our drawings and printouts, and I maybe spared a thought for them when the toner made the pages stick together, but mostly I took all this for granted. Didn’t every household have thousands of pages of three-hole-punched “scratch paper” for throwaway scribbles?—Ed.]

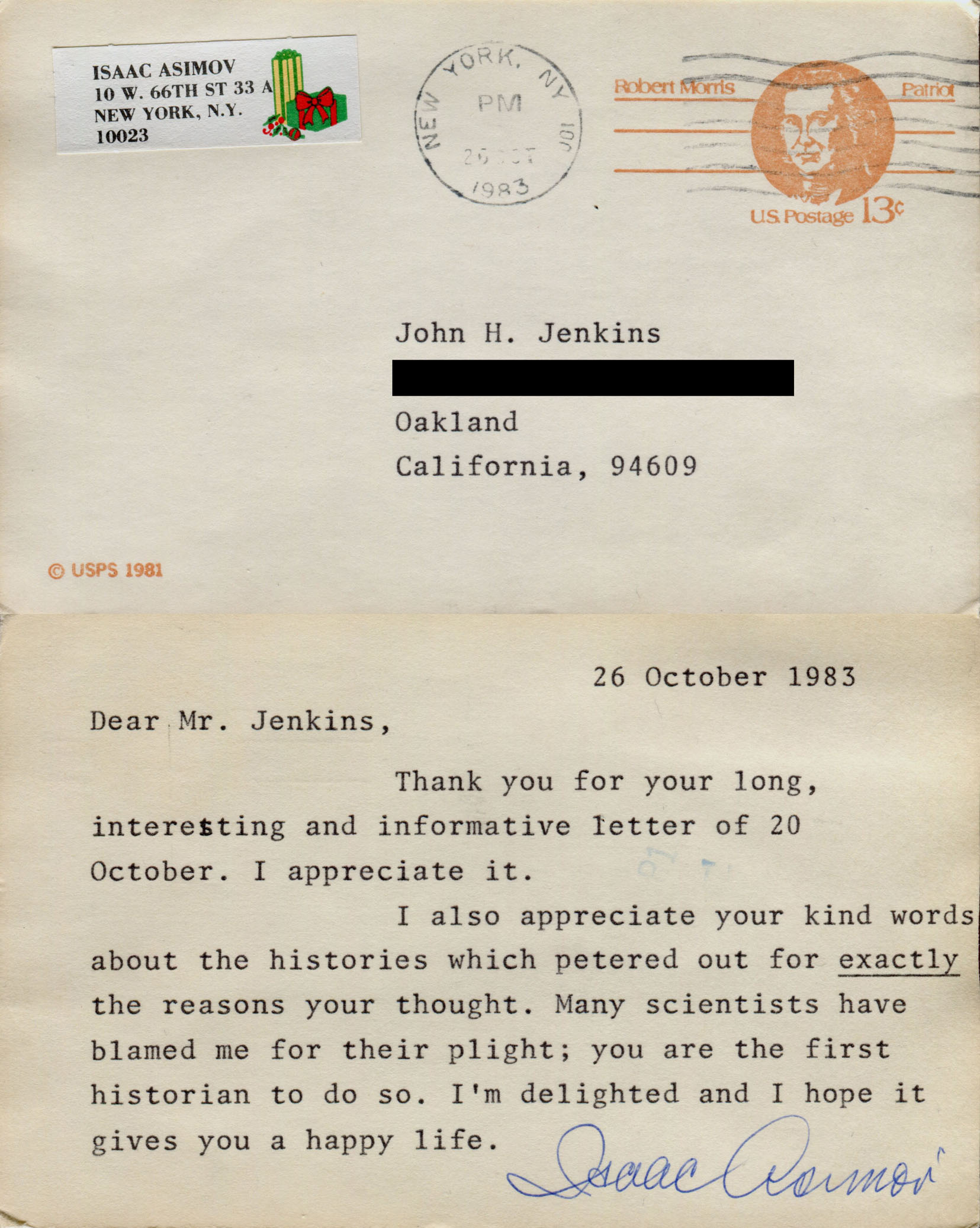

26 October 1983

The following came in the mail yesterday:

[…] With four exceptions […] Asimov has replied to every letter I have written him. Now, I don’t remember clearly either the time or the circumstances of the fourth, so I may be wrong in remembering it at all. There are, at least, three of which I am certain: one requesting permission to write a biography of him, where I specifically stated, “don’t reply if the answer is ‘yes'” so that I would be more likely to get permission; one basically written about the [Mormon] Church which probably offended him badly; and one written from Hong Kong [where Dad was serving as an LDS missionary—Ed.] to which he may have found it difficult to reply. (Well, inconvenient.) Thus, the basic limitation on what Asimov writes to me personally is what I write to him.

Secondly, most of what I wrote to him was in the first glorious realization that he would actually write back. After I got his first post card, I started writing letters to him with machine-gun rapidity. It wasn’t really until his reply number 12 that that died off.

Anyway, since the first item in my Asimov correspondence was the letter I wrote to Doubleday in 1973 asking for his address, I thought that this would be a convenient place to summarize the first ten years of my firing letters off to him and getting little post cards back.

With regards to this latest post card, I would like to say the following by way of explanation: Having recently read his essay “Crowded!” in Science, Numbers, and I, and with the later sequel “More Crowded!” in The Sun Shines Bright in mind, I wrote him at some space about Hong Kong. These two essays are about the world’s “Great Cities,” those with a population of over one million. In neither essay is Hong Kong mentioned, and my letter was an explanation as to why Hong Kong was not mentioned in the sources on which Dr. Asimov based his material and why it should be counted as a Great City.

While I had his attention, moreover, I thanked him for his excellent history books for tennagers [sic]. I expressed dismay that he hasn’t written any for some time, and speculated that perhaps history books for teenagers written by a biochemist cum science fiction writer simply didn’t sell well no matter how well-written, and so Houghton Mifflin, the publisher, lost interest in them. I asked him for more if he could talk H.-M. into it, adding that because of these books, I am a graduate student in history today. (This is true. It was the wonder of The Roman Republic that got me turned on to history as a study. The wonder of that has lasted since the first reading back, I believe, in 1973 […], until just this past month when I have finally decided not after all to become a Roman historian. That’s a lot of impact for one book.)

Anyway, since I was not asking any specific questions, only giving information, I didn’t expect any sort of an answer to come back. After all, Dr. Asimov is a busy man and does get a lot of fan mail. I was therefore surprised to get an answer, and more than a little delighted. It is a particularly nice and ego-satisfying answer, at that.

26 May 1988

I have spoken to Isaac Asimov.

[That’s the whole entry for the day!—Ed.]

6 June 1988

Now, as for the Asimov thing. On Wednesday the 25th of May, […o]n her way home, [my wife H] was listening to an AM radio station, “Magic 61” which plays soporific old-fashioned music which we will both probably love when we’re sixty and seventy, and which [H] rather likes now. She heard an advertisement for a talk show to be broadcast that night, a call-in show, with Asimov as the guest, and suggested that I may want to call in or at least to listen.

Well, I did listen. At first, I wasn’t sure I wanted to call because I wasn’t sure what I would say, but after a while, I thought of a question (namely, “What is the official count?”) and started to call. It was a two-hour show, and I tried repeatedly for over an hour before, fifteen minutes before it was to end, it started to ring. And then it rang for a couple of minutes before someone came on and said, “Hello, what city are you calling from?”

“Berkeley, California,” I said. (Yes, yes, I know it’s Albany, but Berkeley isn’t entirely wrong and has a lot more prestige than Albany.)

“Please turn your radio down,” said the voice, and I knew that I was next.

The only trouble, however, was that I couldn’t tune this particular station in on the clock radio in the study, and so I had the stereo on in the other room. On the other hand, I was on the telephone in the study, since I’d been working […] while I was in here. I called to [H], “[H], turn the radio down!” but she was watching TV in the bedroom while doing some calligraphy, trying to drown out the noise of Asimov’s voice, I guess, and couldn’t hear me. So, I closed the door and got back as far from the door as I could to avoid the confusion of the delayed signal and waited.

Then the moment came. “Berkeley, California,” said the host, “you’re on the air.” At that instant, all rational thought ceased in my mind. I was talking to Isaac Asimov, a demigod whom I had all but worshipped [sic] for most of my life. I don’t have Harlan Ellison’s self-assurance (”You’re not so much,” he is rumored to have said the first time he met Asimov), and at critical moments (e.g., proposing marriage to people, talking to people 270 of whose books I own), my verbal skills vanish and I am left to make incoherent noises.

I stammered out something about having always enjoyed Asimov’s works more than Heinlein’s, with all respect to the late Mr. Heinlein (he died only a couple of weeks ago), since the subject of “is Robert A. Heinlein really the best science fiction writer” came up. Then I think I mentioned that I own 270 of Asimov’s books (it is actually slightly more than that, but I forget the exact number), and asked The Question. “How far behind you am I?” I may have said. “That is, is the figure of 365 which has been given a couple of times during the show accurate?” […]

Well, it turns out it isn’t. Asimov is now up to 390. I got the impression that the host of the show was just reading from the jacket of Prelude to Foundation, which is just out and does have the figure of “over 365” on it.

“So then we can expect Opus 400 within a year?” I asked. Asimov said something vague in acknowledgement that we might, if he lived, and I said “Thank you,” and hung up.

Well, as [H] said, it was a good thing that the calls were anonymous. All that anyone need know is that some jerk from Berkeley, California, made a fool of himself on national radio before the avid ears of millions of listeners, and that said jerk was me can be safely left unknown. I really am embarrassed about the whole thing, and having been so incredibly nervous has certainly robbed the moment of some of its excitement. Still, I have spoken to Asimov on the phone now, and that is something.

(Halfway through, [H] heard a familiar voice and came out. “Is that you?” she asked, just in time to hear me say “Good-bye.” Oh, well.)

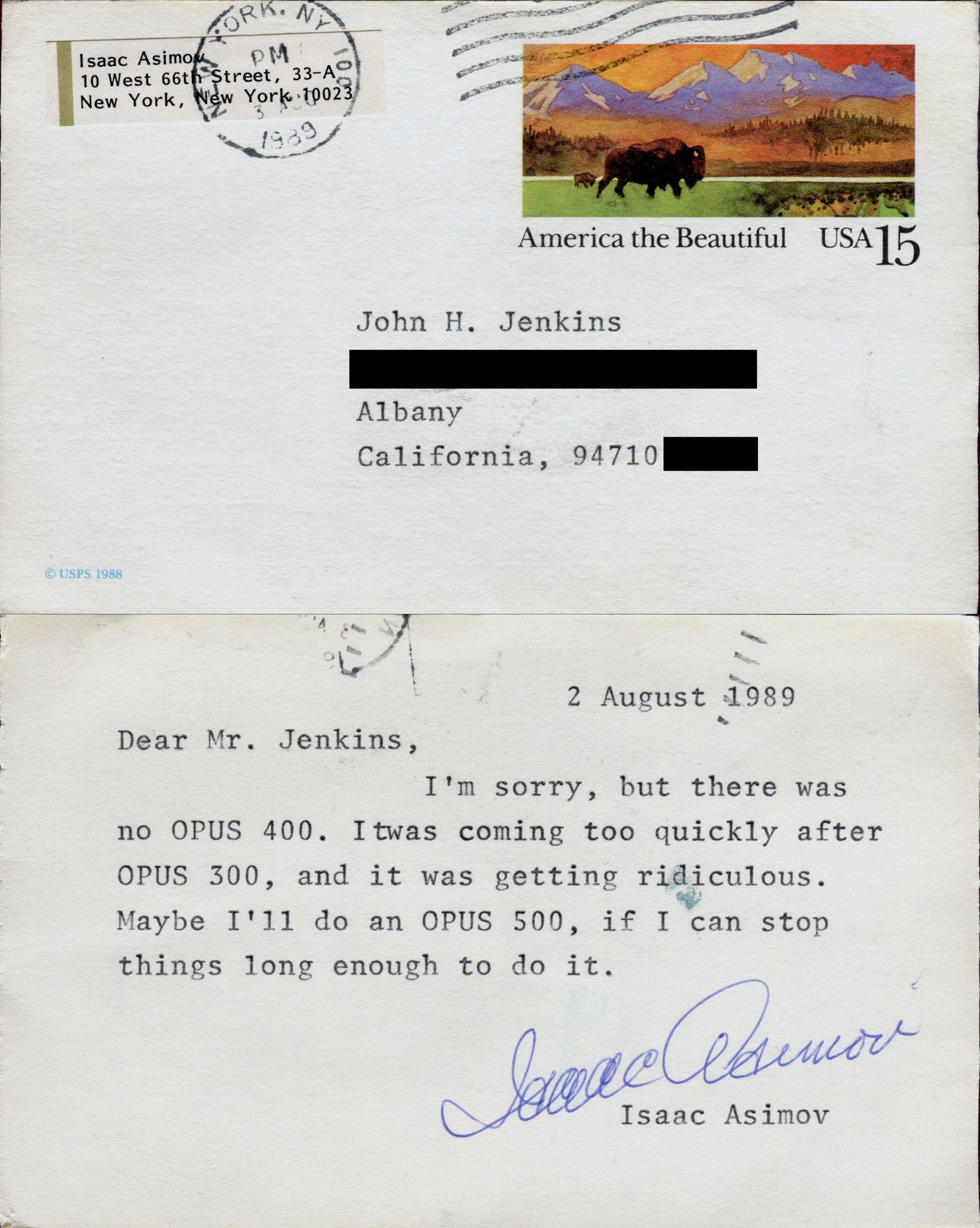

10 September 1989

(TV Guide had in a late-July issue an article by Asimov on the 20th anniversary of the first manned landing on the moon. The article casually mentioned the fact that he was the author of 425 books. Since I knew—from constantly keep up on things in Books in print—that Asimov hasn’t published an Opus 400, I was curious and wrote him to see if I had simply missed it, or Houghton-Mifflin had declined to publish it, or what, and if there might be some other means of finding out what his books #301 to #400 were.)

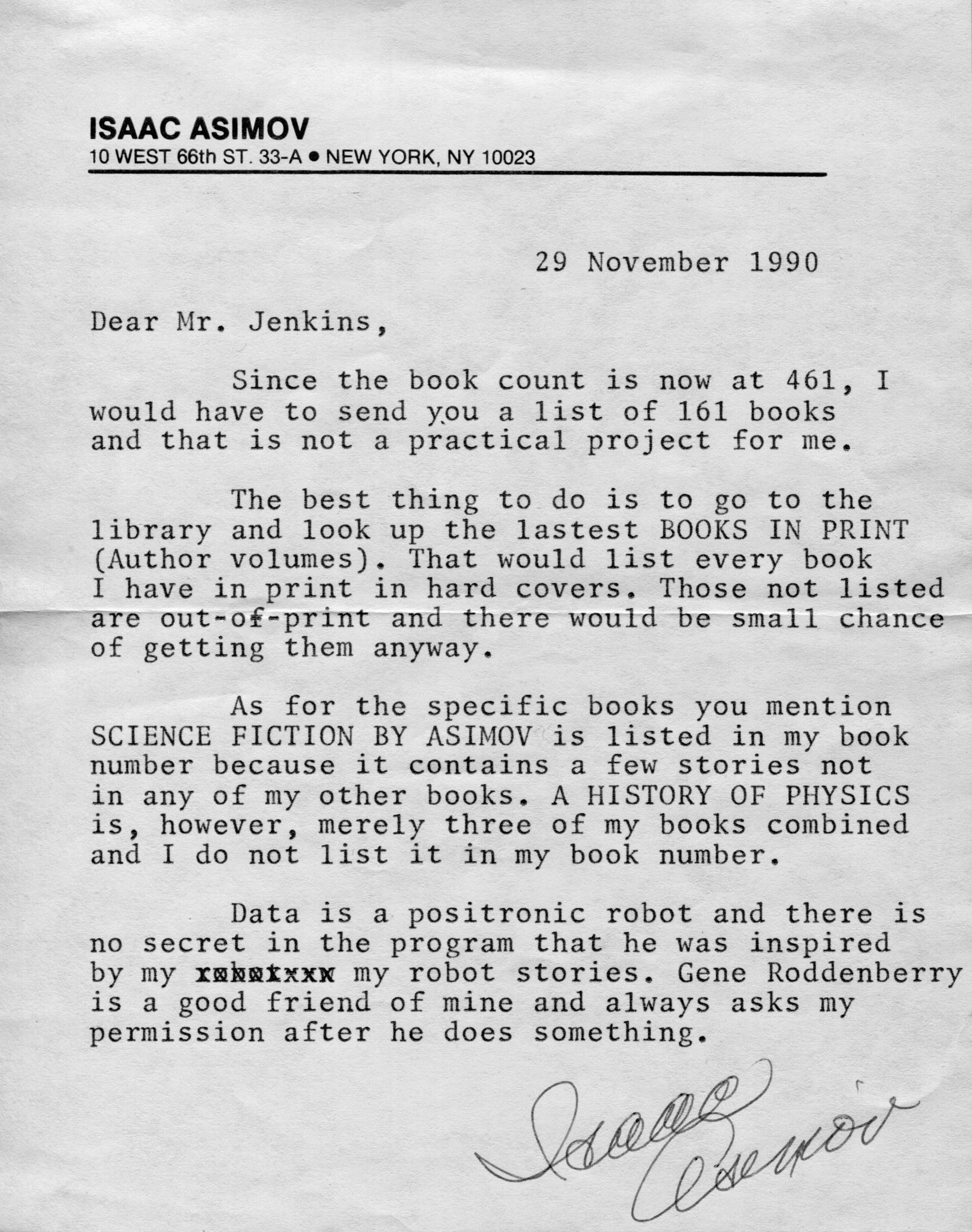

23 December 1990

This is the longest reply I’ve ever received from Asimov to anything I’ve sent him, but it’s also the only time I’ve ever sent him a self-addressed, stamped envelope in which to reply. I was rather hoping that he might keep a running list of his books on his word processor and therefore be able to print one up in a flash to send off—alas, however, it would seem he does not. I did ask him about a couple of books which had (I felt) questionable status and for the current Count, just in case, however. And, as you can tell, while I had his ear, I asked him a question that has been circulating among Star trek: The next generation [sic] fans for some time: The show claims that Data is an “Asimovian” robot in that he is built using positronic circuits. Is he, however, an “Asimovian” robot in the more important sense of having (in any form) the Three Laws of Robotics built into him. Rather frustratingly, Asimov misunderstood my question and failed totally to answer it.

8 April 1992

[Isaac Asimov passed away on 6 April 1992. Dad sent this to the rec.arts.sf.written newsgroup a few days later.—Ed.]

I don’t think that it’s really sunk in for me that Asimov has died. He’s been my favorite writer from the day I first identified one. I’ve been collecting his books for most of my life and spend more time than perhaps I should trying to reread them regularly. (Even at 60 pages a day, it still takes three or four years to make it through just the ones I own!)

I can’t honestly say that his stories are among my favorite science fiction, if only because for the purposes of my reading I classify them as “Asimov” and not “sf”. Although I feel that his later works are not his best and that some of his books are positively bad (even Homer nods), there are innumerable books of his I look eagerly forward to rereading each time, most particularly his F&SF essay collections. His ability to explain, to entertain, to tell stories real and fancied was marvelous, making learning effortless and understanding easy.

His effect on my life was incalculable; there’s so much he introduced me to. He was a catalyst over and over, motivating and encouraging me to read more about everything from the Bible and Shakespeare, through history, down (or is it up?) to Gilbert and Sullivan. My personal philosophy, my major in college, my professional career, all have felt and feel his influence.

I never met him in person. I spoke to him only once, on a radio call-in program. I was so tongue-tied when he came on the line that I could hardly stammer out my question (how many books have you written as of _this_ month?). I wrote him several times, including a number of embarrassingly gushing epistles as a teenager. He didn’t answer them all, but when he did, he was always polite and kind, no matter how obnoxious I might have been.

In particular, I was known in my younger years to try to convince of the errors of his atheistic ways. He did not strike back. As I have grown older, I have come to appreciate that his humanism was based in a fundamental faith in people, that knowledge and understanding, armed with the scientific method, can overcome intolerance, ignorance, and hatred. I came to feel that for Asimov, there are no problems we cannot solve if only we can be prevented from turning against ourselves. As such, he displayed many of the fundamental ethical virtues I value in religion to a far greater extent than too many of the pious.

I will miss him badly.

John H. Jenkins

Afterward

How to bring across the impact Asimov — and Dad — has had on our lives? For me at least, growing up, Asimov was set dressing for Dad’s office, if not the whole house. We had the designated “Asimov bookcases” (and we still call them that, though they contain different books today). Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine came in the mail regularly and was left laying around in various places in the house. A print of Michael Whelan’s Arkady painting, matted and framed, hung on the wall in Dad’s office. Never mind the ubiquitous “scratch paper.” And the books — the sheer, overwhelming quantity of books! We have never in our lives had enough bookshelves for all of Dad’s books. They spilled out into every room in the house, and many had to be stored in boxes long-term, tucked wherever they would be most discreet.

We were taught to treat books with respect (never dogear the pages!), but all of Dad’s books were used. Yes, many were secondhand acquisitions, including library discards, but many were his originals from the 70s and 80s that became worn through normal use. For Dad, collecting books wasn’t about keeping them shrink wrapped on the shelf as part of a pristine set, it was about having them so he could read them and lend them and shove them into bags or coat pockets so they could stow away and fill the idle moments. (And maybe some of the not-so-idle moments, too.)

I think I love reading because it’s the closest we can get to a time machine. I was only five when Asimov died, but I can still get to know him today through his writing, which has lent him a permanence that is impossible for most of us to achieve. Almost all of Asimov’s postcards to Dad are older than I am, but those words, too, return to life when they are read. Each one is a moment caught in amber, a snippet of time sent to the future, connecting Asimov to Dad and to whoever else reads them hereafter.

Dad died a year ago today. He, too, has achieved some small measure of permanence, from this blog, to his Asimov review site, to his personal journal, to his NaNoWriMo fiction, and the letters he sent to his favorite author as a boy. Thank you, Dad, for giving your words to us.